We are crouched along the hallway of Brandon elementary school, our heads tucked between our knees, our fingers laced and cupping the backsides of our tiny skulls. This is rural Minnesota: small-town America where the prairie sweeps toward the Dakotas. Where the winters are long and Paul Harvey is gospel. Where the grocer knows us all by name.

And this is our best plan of defense in the event of nuclear war.

It’s an early memory, and my first indication that the world is not a peaceful place.

***

More than a decade later, I’m in my college dorm, working on a paper about Vonnegut’s Slaughterhouse Five. My parents call. Dad has been activated for Operation Desert Storm. He’s leaving for training in two weeks.

I quit the extracurricular reading group I’m in, which we started at the beginning of the conflict, when it all felt distant from our classroom in rural Wisconsin at what’s affectionately known as “Moo U.” The group was comprised of just two of us students and a professor; students aren’t lining up for extra college work, particularly when it’s intended to encourage critical thinking. I truly wanted to take part, but now can’t imagine discussing the perils of war while my father is fighting one.

Instead, I send him a balloon and a single red rose with a note.

“Kick butt, Dad.”

***

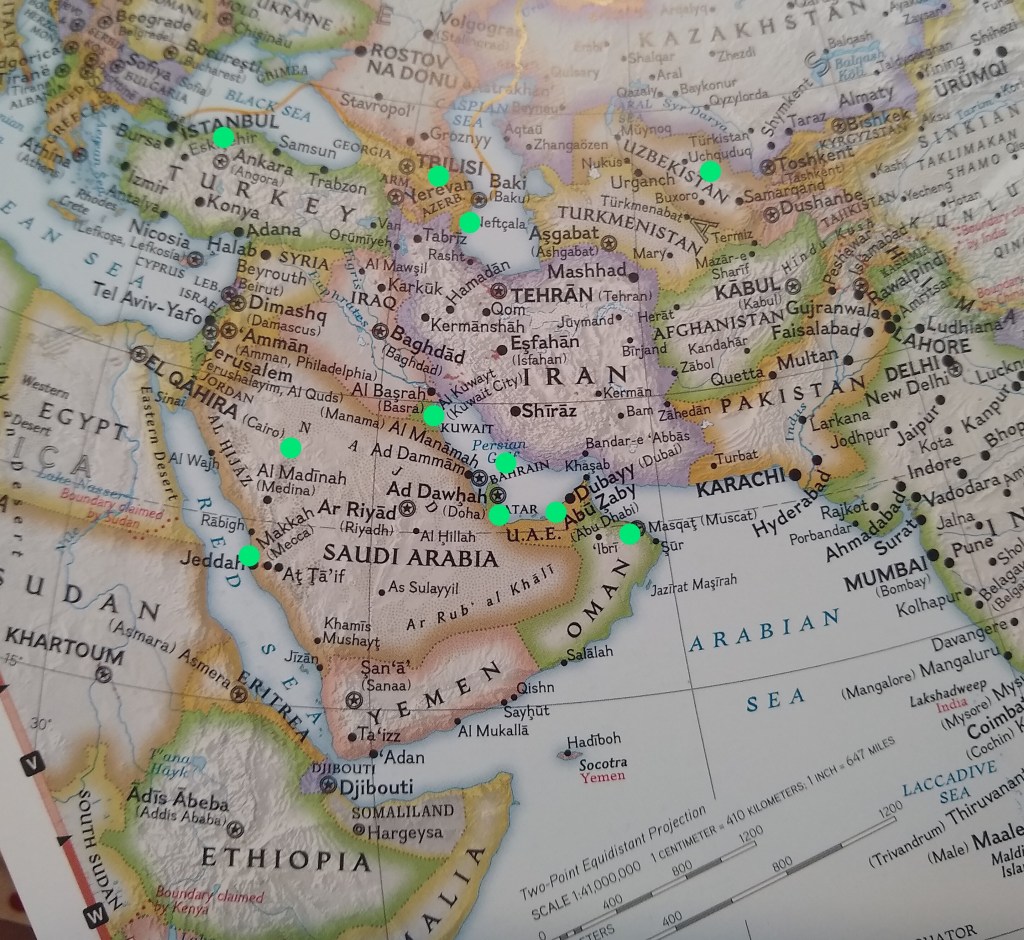

There are problems in the Middle East which I’ve never completely understood, and daresay I never will. They began long before I was born, continued throughout my lifetime, and will probably be avenged long after I’m gone. But I wanted to travel there, to tell the stories of kindness and hospitality that I know exist, which so rarely reach our ears in the West. I wanted to journey to the places so few of us go, to perhaps wedge open the door for others, if they felt similarly curious and intrepid. The plan: to visit a cluster of countries in that part of the globe including UAE, Oman, Bahrain, Qatar, Georgia, Azerbaijan, Uzbekistan and Saudi Arabia. Then, I’d objectively observe and report back, unlike the influencers whose trips are bankrolled by governments. I wanted to experience, first hand, what it was like to be a woman in this part of the world, a Western woman, a female traveler. At more than 50 countries, I figured I had earned a self-directed master’s degree in travel at this point, and now was the time to take on what could amount to my most challenging journey.

But in the months leading up to the trip, so many people looked at me with fear in their eyes when I told them I was traveling to the Middle East, doubt started to drill in. Mom called with concerns, and she almost never calls. In conversation a Vietnam Veteran’s voice took on a sternness I haven’t heard before.

“This is the most scared I’ve been for you,” my husband confessed. But he knows me better than anyone. He knows, it’s probably now or never. And he knows this is about more than travel.

***

I’m surrounded by holy texts, each under glass and open to a single page. And I can’t find my way out of the exhibition. I’m at the Louvre Abu Dhabi, a sprawling, confounding building and I am hungry for art: marble statues and oil paintings that would make me feel something.

But not these feelings. Instead, I’m trapped in “Letters of Light,” an exploration of the interconnectedness of Islam, Judaism and Christianity. I can almost taste the bitterness in my being, the bile of residue religion leaves behind because it too often waters the roots of hatred.

But this exhibition isn’t about that convergence.

This isn’t the experience I came to this part of the world to have. But it is, more than I realize in the moment, the trip that’s found me. Because the world is about to slide into the space where these faith traditions collide, at the bleakest of intersections.

After a requisite pause to appreciate fragments of the Dead Sea Scrolls, I escape to a black hole. It’s a meditative piece by artist Muhannad Shono, entitled, “The Unseen,” sound and threads of light which diverge above and funnel into the darkness of the floor. Beyond this, one can only assume, is the singularity: the compression of the universe into a lone point. Devoid of light and sound. Devoid of matter and dogma. Perhaps even devoid of hate.

I have found the art I craved. I sit in the dark and surrender to the near-nothingness; it feels like peace.

***

A man boards the flight from Abu Dhabi to Muscat, Oman, and I can’t help but notice his t-shirt. It’s emblazoned with two large letters, A and K, an assault rifle filling the negative space between them.

He balances an infant on his arm.

***

Windows look out upon the spooky, crumbling ruins of Al Hamra, Oman, where the streets and walls and rooftops have been washed away and what is left appears to be perpetually eroding. A thin, old man teeters on a walking stick, making his way slowly down the street. He is dressed in a white dishdasha, his feet shuffling along the surface of the sandy streets.

We are at Bait Al Safah, a museum where women have just demonstrated the centuries-old traditional methods of making flatbread and toasting coffee beans.

One painted a line of sandalwood paste across my forehead with her forefinger, historically used to cure headaches, improve concentration and calm the mind. We leaned into one another, smiling at my smartphone while I extended my arm and snapped a photo. I thanked her by buying a small bottle of the perfume she was selling.

“Please, have some more.” Our guide extends a dish toward me, it’s filled with juicy dates, a brown syrup gathering at the bottom of the bowl. My travel companion and I are seated on the floor in this restored 400-year-old mud house, sipping Arabic coffee. Our guide tells us about her plans to study toward a degree in engineering in France, but she’s worried.

“I don’t understand. I accept people for what they are wearing when they come here. Why can’t people accept me?” Her hijab covers her hair, and trails down around her shoulders.

Though I have read the headlines about policies in France which single out people and practices of the Muslim faith tradition, I have no answers for her, so I briefly contemplate mumbling something weakly and instead resolve myself to sipping my coffee in silence as the others continue the conversation. As happens so often, the problems of this world leave me feeling insufficient, at a total loss for words.

Afterward, the haunting sensation of walking through the largely-abandoned village, seeing lives reduced to a pile of sand, a child’s sandal wedged in a washed-out section of the street, it settles in my soul. This is the skeleton of entire lifetimes. It’s the embodiment of the erosion of all things beautiful; it clings to me like the Arabian Peninsula dust that stains the air.

Before bed I scroll the news headlines of the day on my phone, they are all in caps. Hundreds of people at a music festival have been attacked, many killed or taken hostage. It’s October 7th, and I’m just five days in to a 7-week journey throughout the Middle East.

I suddenly feel unmoored.

I turn off my phone, pull the blanket up to my chin and stare at the ceiling, in the midst of all of the unfathomable ruins.

***

The sun hangs low and red in the sky, backlighting ancient church spires, and vendors are packing up their wares for the day: carpets, wine horns, magnets, churchkhela – the knobby sweets that look like hand-dipped candles. My guide Iya and I are strolling through the souvenir market at Svetitskhoveli Square in Mtskheta, Georgia. It’s an easy daytrip from Tbilisi, and–at least on this tourist stretch–gone are the pro-Ukranian flags, the anti-Russian graffiti.

Outside a jewelry shop, a woman cradles a kitten wrapped in soft blankets, its sweet face barely visible. It winces and closes its eyes as if it hurts to simply be. The woman explains through Iya, who translates: the kitten’s leg is broken. They don’t know if she’s going to survive.

***

My travel companion and I decide to part ways in Istanbul. She’s been called back to work due to rising tensions in the Middle East. I decide to head to the European Union, so I abandon my return flight to Bahrain. My hastily-booked hotel is nestled among the historic streets of the Sultanahmet neighborhood, where the scent of roasting meats hangs thick and tempting in the air, wrestling with incense, fresh coffee, fruity shisha.

Straddling the border between the Middle East and Europe, I opt to treat myself to an expensive dinner cruise on the Bosphorus Strait. A celebratory farewell. The brochure promises food and drinks and dancing, but the bus is late.

Very late.

As I sit and wait, crowds stream by: families with strollers, women in burqas holding Palestinian flags. The air feels charged, crackly. I poke at my phone and find there’s a protest at Hagia Sophia Grand Masque, a kilometer away.

I am American, which is to say I have been both protestor and protested. And I’m increasingly aware of how unsavory it is to go on a boat cruise in the midst of the madness. I suggest I should maybe cancel my tour, but the front desk worker says no, they’re on their way. And of course I understand. The tourism machine, like the war machine, stops for no one.

Nearly two hours overdue, the tour guide shows up at the hotel. “That’s him,” the front desk worker at my hotel points to a man who is staring at his phone, who darts off into the crowd without even looking my way. I follow him, weaving between the protestors, rushing to keep up so I don’t lose him in the winding streets. After 15 minutes he still hasn’t looked my way, and I start to doubt I’m following the right person.

“Sir?” I yell after him. Does he even know I’m here? There’s no response. “Sir!”

He waves his arm impatiently, and grunts, never looking back.

A luxury coach bus rises before us, above the swarming activists. I board, and glance toward the other passengers, some wide eyed, others looking tired, bored. We inch along in the dense traffic. Now that I can see his profile, I notice the tour guide is visibly pissed. His phone is constantly ringing. He walks through the bus with a clipboard, asking, “Alk-hol?” Scrawling notes as he determines who among us has paid the extra money for drinks. I have.

Our bus pulls over on the side of a busy roadway, cars and vans and buses speeding by. We disembark and follow our guide across the street, dodging traffic in a terrifying, real-life game of Frogger. He stops us in the middle; there’s no median but simply a curb that’s too high for my short legs to climb, and we stand there in the darkness where surely these drivers can’t see us. I see the guide sipping something dark red from a highball glass, and I think, good for him.

We wait on shore, watching the garishly-lit boats bobbing on the choppy water. One comes to the dock, and as we board, a tourist who is bent over and holding her stomach glances warily in our direction, then covers her face with her hand. We are ushered inside, to the last table in the room. The party has happened without us, and the performers are already sweating through their costumes. They prance to the front of the room with great earnestness, but I’m seated facing the opposite direction, and they’re 20 tables or more behind me, so even if I crane my neck there’s little chance of seeing them.

I focus instead on the bartenders and tour guides who have gathered in back and are commiserating, some looking dissociated. A dancer, waiting with disinterest for her next number, twirls a brown tendril of her hair and examines it for split ends. Food appears without fanfare, the music changes and new performers take the place of the others, whose smiles fade from their faces before they even pass our table. We fight to get the waiter’s attention, to have our glasses filled and refilled, which they seem reticent to do. Desert comes, and it’s two slices of orange and two wedges of green apple, followed by children who are trying to sell us ice cream for an additional charge.

The emcee chirps into the mic, “How is everyone doing tonight? Are you ready to party?!?!” He waits the requisite time before showing his preconceived disappointment with our response. “I CAN’T HEAR YOUUUUU….”

The giggle bubbles up without warning. The absurdity of it overwhelms me and I’m powerless to stop myself laughing. Somewhere, not very far from here, there is a war going on. People were murdered, some taken hostage. Others are being bombed. Women were paraded in the streets, blood dripping down their legs. And yet here we are, on the Bosporus Strait, on an overpriced tour with mediocre food and terrible service. I can’t even process the disconnect, so I laugh. Two men at the table look at me as if I’ve lost my mind, and maybe I have.

“This is so ridiculous,” I flounder as I to explain myself. “There’s a war going on…and here we are.” I motion to the room, the people who are dancing as fast as they can, the exhausted tour guides, the half-eaten plates of food.

And then the almost imperceptible barriers between us disintegrate. The eyes I’d locked with on the bus warm and smile, and we announce our countries: Canada, Australia, Mauritius, Cuba, Russia, America. And we fall into the casual conversation that happens between travelers. Canada talks of beating leukemia through diet, and I recycle something I read online that Canada must feel like an apartment above a meth lab. And we all easily agree that the world is complicated. Canada and Australia, a couple, remark that much of the Middle East you can’t travel right now, so they are thinking of traveling to New York and New Mexico. And Russia, who seemed embarassed to reveal her country of origin, says she’s a photographer. She asks if I’m on Instagram; I tell her no, I blew it up. I don’t tell her about my deep distrust of social media, how I feel the fissures it creates between us. I don’t tell her how it’s the front lines of the war on truth, how we’re all victims of it and how I’ve opted for the most part to be a social media refugee. No one cares about refugees. She has three accounts and her son is a model and has his own account. She shows me his photo, he’s in a puffer vest, posing. He’s young and doesn’t yet know how complicated the world is.

A belly dancer in a green, glittery, barely-there costume flirts with the men in the front of the room, compels them to dance. She selects partner after partner, then disposes of them to their seats, working the room. And then, she’s beside me, tickling me under the chin suggestively, thrusting her breasts toward us. I reach into my purse for business cards to give to the travelers, and at that moment the tip tambourine comes out. When she determines there’s no gratuity to squeeze from the table that hasn’t seen anything but her tarty flash of tinsel, she moves on.

I scale the steps to the top deck, where the breeze is blowing and smells of second-hand smoke instead of sweat and onions. The boat is crowned with metalwork of a dolphin in a circle. Two Russian men puffing on cigarettes invite me to their bench, and I smile and nod, gratefully accepting a seat. Two grinning, Rubenesque tourists summit the stairs and I wave them over to the last remaining spaces, beside me.

Our vessel coasts beneath the Bosphorus Bridge illuminated in red, which makes it look somewhat like San Francisco’s Golden Gate. I’m so far from that world. And I wonder if we can even build a bridge strong enough to traverse all of this.

***

I, alone, am incapable of stopping the waves and undertows of this world. Like all of us, I am but a grain of sand: insignificant and temporary and suspended. War, on the other hand, is all powerful. Wars sell t-shirts and weapons and elections and religions. (Or is it the other way around?) More, we are all compelled to choose sides: either/or, and never is peace part of the consideration, it seems.

Yet peace is the most patient of options, it’s always there. Peacemakers far smarter than me have appealed to the masses to put down their proverbial guns for eons. And still, so few see it as a viable solution. Is it because there’s always a bottomless purse for war, and little to no funding for the tools we have to prevent war? Like education. Like art. Like literature. Like justice. Like travel. Perhaps it’s because hate is easier, war is easier. Peace-seekers are painted as weaklings, but in my mind, peace is infinitely harder than war. It means pausing when you want to fight. It means taking time to think and talk rather than striking blindly out, railing against whatever triggers you. It means swallowing back your pain time and again, working on healing yourself and vowing not to transfer that pain to others, even those you might perceive to be your enemy. Neither online, nor in the flesh. Peace is the most difficult of paths. There’s a member of my family who has spent his life advocating for peace, but he has been estranged from all of us for a decade now. And isn’t that a war too? How do we pursue peace outside our homes if we don’t have it within our walls, least of all within ourselves?

I know none of us have been given a syllabus, the grand assignment of this existence. But I’m pretty damn sure of one thing: we’re not supposed to murder one another’s children.

***

The DJ plays a familiar-sounding song. Australia has grabbed my hand and Mauritius at last is showing what he can do on the dance floor, and Canada is swept up with us, unwilling and willing at the same time. And Russia is leaning into Cuba, they share a sweet moment and then it’s gone. And maybe it’s okay to dance when the world is burning, it’s a question I’ve struggled with most if not all of my life. Because if you don’t dance, you’re just consumed by the fire, crumbling to ash. And the fire is always burning. Always. After all, when has there ever truly been peace? I don’t have it all figured out yet, but maybe some of the answers are here on this boat, this vessel where we all grin and jump and sing and sweat together.

The lights come on and the music changes in the universal sign for, “You don’t have to go home, but you can’t stay here.” Australia gives me a firm embrace and kisses my cheek. I’m glowing with happiness, because in spite of it all, everything actually was great on the Bosphorus Strait.

We funnel out, and I wish them good luck with everything, because there are no words sufficient to describe the reality we are about to re-enter.

It’s well past midnight and I have to get to the airport in four hours to catch my flight out of Turkey, to head toward presumably safer soils, though I’m not entirely convinced. Hate needs no passport. The tour bus drops me off on the sloppy fringes of the old town, vestiges of the protest still clinging to the cobblestones. A kitten licks vomit off the sidewalk. I start walking as if I know where I’m going, which I do not. But I’m finding my way, as I always do. No matter how tangled the streets are, or how ugly are the truths that we find, somehow we all find our way.

***

It’s a cool, rainy day in Brussels, and I’m drinking an IPA and eating impossibly crispy fries and mayo in a pub on the main pedestrian drag. The Middle East seems far away.

From here, I’ll go to Krakow. But first, a man will fire an AR-15 on Swedish nationals in this very neighborhood, killing two and injuring a third. Retaliation for wounds of the past, nation versus nation, religion versus religion, converging yet again in the ways no one wants to talk about. Police will search for him overnight, and shoot him dead in a cafe the following day.

My husband texts, “Are you going to Auschwitz?”

And I’m suddenly overcome by a yearning for a peace I’ve never known. A peace that perhaps has never existed in this life, in this world. Not in elementary school. Not in college. Not now, in this restaurant. The realization swamps me and pulls me under. I won’t go to Auschwitz, I can’t. I’ve been to Yad Vashem. Toul Sleng and S-21. Con Thien Firebase in Vietnam. I’m not a person who hides from these things. Or am I? I simply can’t help but feel that we’ve gone through this before and yet we’ve learned nothing. We repeat the same patterns over and over again: we go to war, we murder one another, and we build monuments to the dead which we then charge a fee to tourists to visit. Eventually the whole world will be a monument to death and retaliation, with an attached gift shop.

The server sees the tears in my eyes. The guilt. The sense of personal failure. The lostness. He gives me three lollipops when I close my tab.

That night as I wander the city, I see a man on his knees in the middle of a walkway, his head in his hands. No one is paying any attention to him. I awkwardly put my hand on his shoulder to offer a modicum of comfort, to recognize his humanity and perhaps to reassure myself of mine. And I give him what I can from my pocket, which isn’t nothing, but is insufficient to fight whatever wars envelop him. The next morning at Charleroi Airport, after a nod from their mother, I give the lollipops to children, a little boy and his baby sister, who are patiently awaiting their flight.

If the interim between battles is peace, it is fragile at best. It is the kitten at the market, injured, like all of us limping through this life. And none of us know if she’s going to make it. Some would crush it, rather than carry it. But what if, instead, we cradled her like the precious, fleeting notion she is. What if we made it our personal responsibility to nurse her back to health in whatever little ways we can? Helping someone in their personal battles. Mending the broken parts of our families and ourselves. Finding joy where we can, in the midst of the psychological and physical ruins of this world. Acknowledging and re-imagining the forces that feed hatred and division. I am a grain of sand today and dust tomorrow: a fragment of that milky silt that clouded the air when I first landed in the Middle East. But what if I dropped myself into the sea of life with as much love as I can muster from my personal brokenness? What if I comforted or even healed one shattered peace? Would it make any difference in the world? Any at all?

I left the Middle East on October 15, five weeks earlier than I’d planned. And though this isn’t about me, I regret that I won’t be able to tell the stories I wanted to tell. Maybe I’ll get back there. Maybe someday. For now, though, peace seems so very far away, on the other side of an incomprehensible black hole, as humankind awaits the ultimate convergence: the spiritual singularity of peace.

Have you enjoyed our travel content? You can support our work here.

Charish Badzinski is an explorer and award-winning features, food and travel writer. When she isn’t working to build her blog: Rollerbag Goddess Rolls the World, she applies her worldview to her small business, Rollerbag Goddess Global Communications, providing powerful storytelling to her clients.

She is currently working on a collection of her travel essays entitled, Sand Dunes, Sea Salt and Stardust.

Posts on the Rollerbag Goddess Rolls the World travel blog are never sponsored and have no affiliate links, so you know you will get an honest review, every time.

Read more about Charish Badzinski’s professional experience in marketing, public relations and writing.

Discover more from Rollerbag Goddess Global Communications

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

I Love you and your writing and you have made me sad and happy and crying all at the same time.

I miss your regular stories of travel since I don’t anymore.

I wish you and the entire world peace…..

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you so much! It means a lot to me that the piece resonated with you! I’m so sorry to hear you don’t travel anymore, but I am glad you are finding ways to feed that wanderlust online. Wishing you and the poodles and the world peace in 2024 and beyond.

LikeLike

We are happy and I am good. Working for all the causes in my hometown! I do travel once a year to see family on both sides… Wishing you Love and Joy and Peace as well

LikeLike

Loved studying about your Bosphorus Strait adventure! Your vivid descriptions and charming storytelling transported me to the bustling streets of Istanbul and the serene splendor of the waterway. Thank you for sharing your top notch trip with us!

LikeLike