“Travel should be about looking deeper into the world at large, into oneself.”

– Paul Theroux

I traveled to Bali not for the beaches, not for the parties, but for the silence. I traveled there to give myself permission to log off, power down, and go within. To grieve what I needed to grieve. To learn to love again where love had been lost. To forgive where anger had taken up residence. To heal.

Did I need to travel halfway across the world to find silence? Absolutely not. After all, there are silent retreat centers and sanctuaries everywhere, and it’s even possible to practice silence and mindfulness in your own home. But there’s something inherently powerful about setting the intention to heal, and making a pilgrimage toward it. Every step you take toward the intended silence prepares your soul for the work that must be done.

Make no mistake about it, true silence is work. Tapping into our inner wisdom by eschewing the distractions that make up the bulk of our days is difficult, particularly when we’ve actively leveraged those distractions to tamp down our pain. Maybe most of us realize that, as so many people have told me they could never do a silent retreat. Silence is uncomfortable at times, peaceful at others, and intermittently excruciating. But silence and mindfulness are so very necessary in our incessantly noisy world, where we distract ourselves every second of every day with books and devices and social media and work and busyness. In silence we can begin to heal wounds of our past, work through the very things we try so hard to distract ourselves from, and access our inner truths.

My First Time at Bali Silent Retreat

The first time I traveled to Bali Silent Retreat, I had the hubris to think I had my head on straight, and no work to do. And the silence enabled me to cling to this mindset; I never felt challenged or wizened during my brief time there. I could only squeeze in three days in my travels, so I went with the intention of meditating, resting and feeding my body the gorgeous organic, locally-grown produce prepared by the Bali Silent Retreat kitchen angels. It was February of 2020. I flew into Denpasar’s Ngurah Rai Airport , and the driver I’d pre-arranged through the retreat center met me at the arrivals gate.

Bali funeral season was in full swing so traffic was heavy, and we inched along the narrow, winding roads of the island. I asked my driver if we could stop for lunch, and he took me to a stand alongside the road serving up fresh, spicy chicken satay and soup. We gobbled it up while sitting at a picnic table shaded from the Balinese sunshine, the cart owner looking on with obvious pride.

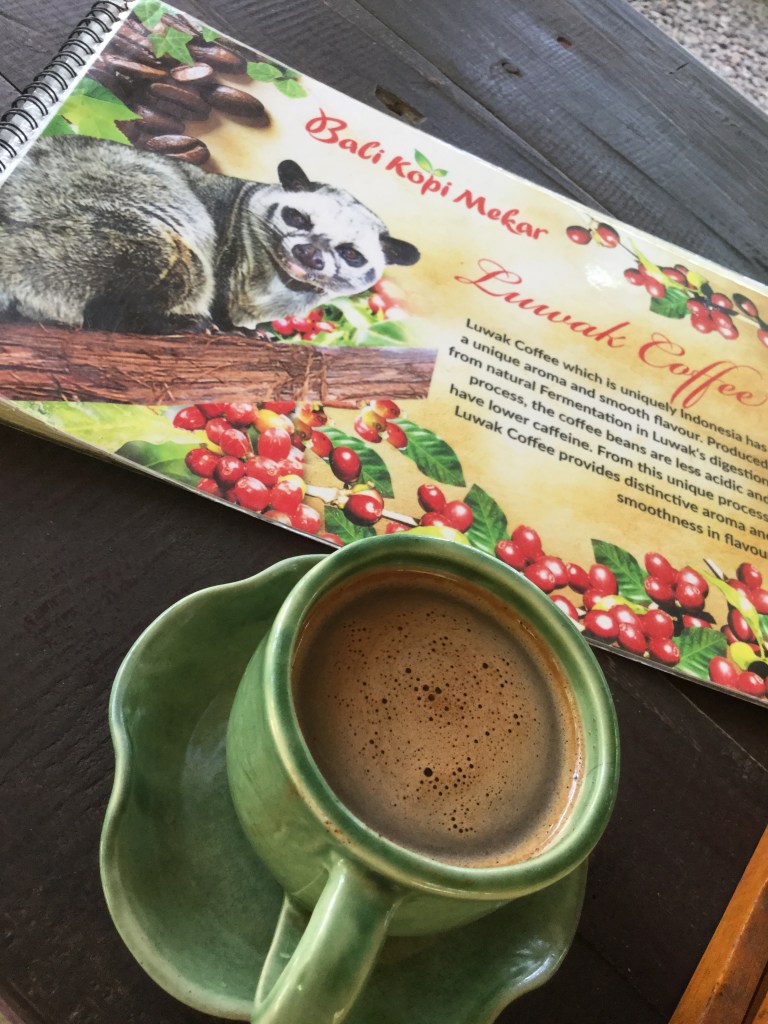

As we continued on, my driver asked if I’d like to stop at a place where I could try kopi luwak, coffee made from beans which are first consumed and pooped out by civets. I was up for anything, even a predictably tourist-trappy pause (though in retrospect and with more understanding of how civets are treated, not sure I’d make this choice again).

“Do not worry madam,” said the well-dressed guide in formal English, “the beans are very clean and safe.”

The tea samples were interesting; the coffee was delicious. I bought two small, overpriced bags of kopi luwak beans: one a gift for my mother, the other for myself.

We continued to the silent retreat center, our car curling around terraced rice paddies and past aged Hindu temples weathered and stained dark, stern-faced stone spirits wrapped in colorful cloths giving us the side-eye. Curved bamboo poles known as penjor waved to us over the narrow streets.

“Have you ever been to the United States?” I asked my driver. He shook his head.

“Maybe someday?” I said encouragingly, and he laughed in the way people do when something is unthinkable, or impossible. Even the budget traveler who pays attention is frequently humbled by their comparative wealth as seen through the eyes of those she meets on the road.

I’d chosen the most ascetic room option at Bali Silent Retreat, an upper-level single room with no fourth wall, just an unobstructed view of the expansive jungle and a screen that could be lowered if needed (current rates $45/night, plus $47 food and programs day pass, and service fees and taxes). That view through the open balcony was what had spoken to me.

I’ve never stayed at an Ashram so I have no point of reference except Eat, Pray, Love, but organizers say Bali Silent Retreat operates similarly to an Ashram, where retreatants are responsible for keeping their own spaces and dishes clean. The retreat center is non-denominational, non-dogmatic and welcoming of retreatants with differing faith traditions or none at all as the case may be. The center is driven by ecological and sustainable practices, with massive amounts of food grown on the property, dragonfruit and rice and greens, all of which is served to retreatants. The property is solar powered, so there are no outlets in the rooms for charging phones and other devices (retreatants are issued a locker and key and encouraged to squirrel away their devices to achieve the greatest benefits of the retreat). Attendees are issued a cotton kimono, towel and washcloth, a journal and pen, eco-friendly soap and fresh bedding. You are expected to make your own bed, clean your own room as needed, and strip the bedding when it’s time to go.

All programming is optional, and the retreat is self-directed, so you can do as much or as little as you wish. Meditation and yoga are offered twice a day. Beautifully-prepared meals are served three times a day and retreatants are summoned to the table with a wooden bell, the crack of which cuts through the dense Bali greenery and can be heard in the rooms. Attendees can hike jungle paths to the “crying bench” on a river bank, they can walk a crystal-framed labyrinth, or meditate in an ancient, open-air temple while being showered by water from a holy spring. There’s a library on site, star gazing beds, and nearby rice fields to explore.

A shuttle is provided weekdays to off-site hot springs. There, the silence is no longer mandatory and frequently broken, and WIFI is available for those who just need a little fix. On day two of my silent retreat, I regrettably had to go to the hot springs to download and print my visa for the next leg of my journey: Myanmar (pre-coup). Already the world was intruding upon my retreat. Already I was pulled into the future, no longer present to the moment at hand. Breaking the silence felt like an insult, maybe even an assault. I had wanted to stay in silence and disconnection, I had craved it, and I had no choice but to break it.

A rainstorm busted through the sky on my last day, and with my room open to the jungle canopy, I could hear every raindrop tapping on my exposed heart. I was fully present to it, and it felt like a gift so profound words are insufficient to describe it.

I knew I had to come back.

And then, too soon, it was over. I left feeling unfinished, that perhaps I’d had more work to do than I’d admitted to myself. Yet my experience in those three short days allowed me some insights into how to integrate mindfulness into my daily life at home.

Unbeknownst to me, these skills would become important in the near future, when the global pandemic took hold.

Returning to Bali Silent Retreat

Just over two years later in 2022, I returned to Bali with the intention of being in silent retreat for a full two weeks. Unlike my first visit, this time I knew I had a lot of work to do and I wanted to allow sufficient time for it. The pandemic had worn me down, rendering me angry, bitter, spiritually depleted and professionally burned out. Work and doomscrolling had been my whole world for two years. I desperately needed to make peace with my fellow human beings. I needed to recalibrate after sacrificing my wellbeing and losing my balance. I hungered for clarity on my professional future; I’d lost all passion and enthusiasm for my work. Those were my intentions. I hoped two weeks was enough time to get myself back to good.

Again, what hubris. Is it a uniquely American quality that we think we can rush healing along on a timeline? Two weeks is nothing. I’m surprised I couldn’t hear the universe laughing at me.

My flight arrived into Denpasar too late to check in to Bali Silent Retreat, so I spent a night in town, wrestled with cash card issues, and scrounged up enough cash to get a few essentials at a 7/11. A pack of street dogs began sparring as I walked back to my hotel. They looked rough: feral and hungry. Two limped, others had open, weeping sores.

I had a video call with my husband, and I felt fragile when we disconnected, knowing I wouldn’t be able to call or even text him for two weeks. I tried sleeping and failed. I felt emotional and assumed it was my latent stuff ready to be purged at the retreat, waiting impatiently in the wings. I had numbed myself with too much food, alcohol and social media for the duration of the pandemic. As those crutches fell away, the mess previously hidden behind these unhealthy coping mechanisms emerged like one of those ratty and bleeding street dogs. It was time to fight.

The hotel offered a full breakfast buffet, but I had no stomach for it, though I reverently sipped the last cup of coffee I would have for a couple of weeks. I packed my things, and my hired driver soon arrived. This time we didn’t stop for civet-digested coffee or satay. Recent rains had washed out a major road so the drive was longer than usual, but I arrived at Bali Silent Retreat in time for their buffet lunch. I checked in to my second-floor single, again with a wall open to the jungle canopy. It felt even smaller and simpler than I remembered.

I made my bed and napped, rose for dinner and then walked to the Agnihotra Ceremony, a ceremony based in Ayurveda during which attendees gather around a small, flaming pyramid and chant in Sanskrit. One by one, we fed the fire what no longer served us and released it, the sounds of the jungle discordant with our chanting. When it was my turn to approach the fire, I was overcome with emotion. So much of the past two years had been unspeakably hard. At the fire pyramid, it was clear to me it was all suffering and anger. I held my intentions and those of my friends in my heart, willing the transformation the ceremony and this place promised.

And then, the work began, though it came innocuously dressed as quiet and yoga and meditation and mindfulness. I detoxed from so many aspects of day-to-day life that I drew up a list of them: devices, meat, dairy, alcohol, caffeine, spoken words, processed foods, social media, news, toxins (all food and personal care products at the retreat are organic), email, work, America, violence, calendars and clocks. I am not a napper, but perhaps as a result of detoxing from these things, I found daily napping came easily and naturally to me, sometimes twice a day, and it felt good.

By day three I wrote in my journal: “I’m not sure if I’ve figured anything out yet.” I’d been traveling for two months at that point, on sabbatical. But I did have a realization, intertwined with missing my husband: too many of the couples I’ve known in my life seem to have too little time. So many have had to say goodbye too soon. And I vowed to make the most of the time my husband and I have together, holding out hope that I would outlive him so that he doesn’t have to suffer that loss. Maybe that was enough work for the day, or even for three days.

It rained at day’s end and into the night. I made myself a cup of tea with fresh turmeric, ginger and lime, and sipped it while I stared out my open wall to the world and listened to the timpani drumbeat of raindrops on the trees.

An intermittent, piercing pain had been bothering me while walking, but only when I hit upon a walkway stone at a particular angle. I’d examined my shoes time and again with no luck, willing the evildoing thorn to show itself. When it happened again, it occurred to me it might be remnants of a seashell that had lodged itself in the soft arch of my foot during my travels in Malaysia. Only in silence do we awaken to the lessons in such everyday occurrences. I had assumed the cause of my suffering was external, but it was actually within me all along.

In addition to daily meditation and yoga, which often left me sore, I sometimes walked the crystal labyrinth, or the mosquito-infested jungle pathway to the “crying bench.” But my favorite corner of this quiet part of the world was the outdoor temple for water meditation. I’d carefully choose a sarong from those provided, descend the mossy, slippery steps to the temple and bow my head to clear the greenery that draped over the walkway. The sound of cascading water was the only hymn. Stone goddesses overgrown with moss and plants poured holy spring water onto humble wooden benches. I took a seat and allowed the cold water to splash over my head, willing it to wash away the heaviness I’d gathered over the years, the heaviness we all carried in the wake of our global upheaval.

The second-floor single rooms are open to one another; the wall does not extend to the roof, and therefore retreatants share air. I’d made it through two years of the pandemic without getting Covid, and I’d remained careful even as the world had begun reopening its borders, even as I’d returned to travel. But on day five at Bali Silent Retreat the woman in the room next to me had begun coughing incessantly. And another down the hall was coughing in tandem. Covid or not, I didn’t want what they had, so I resolved to upgrade my accommodation as soon as possible.

I inquired at the main office, and they had a deluxe single room available for the remainder of my stay (current rate: $75/night, plus food and activities day pass and fees). In the pauper’s room, I’d had a bed, nightstand and wooden chair. In the new room I had many times more space with a sitting area, a meditation mat, a comfy chair and footstool, a desk, a big shower and bathroom, my own water jug and a full-length mirror. In the larger room ginger tea was delivered every morning before the gong rang for yoga and meditation. No one could hear me pee aside from the one retreatant in the same duplex. Though I’d booked the room only an hour before, there was already a sign over the door with my name on it. It felt comparatively luxurious, though I must admit I missed having a fourth wall open to the jungle and the breezes it had afforded me.

The room change coincided with the anniversary of a ruptured appendix and emergency surgery which had saved my life. Though I’d thought I’d put it behind me, being in silence for several days had left me feeling fragile, with the realization that I could have died. And yet, here I was, alive, in Bali.

I felt sore from yoga and emotionally wrung out, so I opted to skip group classes that day. Our instructor had said, “Honor your relationship with your body.” I elected to meditate alone in my new space. A light rain began to fall, and it was lovely. In the distance I could hear drums and a pinging noise, perhaps a festival in town. Occasionally I could hear a small scooter pass the vast property. But otherwise, the soundtrack of Bali Silent Retreat was raindrops and birds and frogs.

I took a nap. I guess I’d become a person who naps. And I could tell I was falling into step with mindfulness, just five days in to my two-week retreat. I was paying more attention even when engaging in simple tasks like washing dishes or walking. And sometimes I would just spend time looking out at the jungle, doing nothing else.

One day at lunch at the retreat lodge, as I was seated alone on a counter overlooking rice terraces, a gecko approached. It surveyed me with its big eyes for a long time. I put a small piece of a taro chip out for it. In time, the gecko drew closer, cautiously, and took a taste of it. I could hear the crunch as its jaw bit down on the chip. But the gecko apparently didn’t care for the chip, and after spitting it out, it took a closer look at me. So I took a crumb of bread from my peanut butter sandwich and set it out to see if it was more palatable to the adorable beggar. In time, the gecko tried the piece of bread and found it to its liking, greedily munching the cottony ball as it watched me. I put out more crumbs, as the gecko took a bit in its mouth to a private place to dine in solitude. It returned moments later to find even more bread set out, and helped itself to another piece. A gecko friend popped in, this one slightly smaller, to see what the fuss was about. The senior gecko sprinted off with the bread, and the other skittered away. They didn’t reappear, so I wandered over to the little library on the other side of the room to scan the titles and run my fingers along the bindings. When I returned, my gecko friend was peering over the window ledge, but wandered no closer in spite of the buffet I’d set out. And in the meantime 100 tiny ants had marched to my plate to help me finish my lunch. I swept up the leavings with the palm of my hand and washed my dishes.

Two days after the appendix surgery anniversary, it was the anniversary of my father’s death, and a weight descended upon me that I couldn’t shake. Half way through morning meditation, sitting in the dark before sunrise, I had a vision. It was newborn me, and my young father was cradling me in his arms, crying with joy, sucking on my feet and making me giggle. The vision felt like a priceless gift; I could feel his joy. Had my father wept when I was born? If he had, I’d never known it. But in that moment I knew. Right there in meditation, in the circle of souls sitting in the bale, tears coursed silently down my cheeks.

I decided to go to the hot springs, the first time since my return to Bali Silent Retreat. The transport van included me, an Australian, a New Zealander, a New York expat who now calls Bali home, A German, and a Dutchman. Now free of the expectation of silence, I heard their voices and accents for the first time, which was jarring, surprising and strange.

I dipped in a few of the pools at the hot springs, a vast and chilly pool at the top and smaller pools cascading down the hillside. Slowly and deliberately making my way down toward the river.

“It’s real,” said the woman from New Zealand in wonder; she was sitting in a pool with bubbles rising up from the bottom, bursting at the surface. I joined her; the bottom was soft and there was no eggy, sulfuric smell as I was used to experiencing at hot springs. Soon we were joined by the German, the Dutchman and the expat. The Dutchman joked that the bubbles rising from the bottom of the pool were because he was farting.

In time the travelers wandered off to other pools and I was left to chat with the expat. That very morning, I had wordlessly given her a blue flower that had fallen on the pathway to the lodge.

She told me she volunteered a day a week to help with the dogs of Bali. She said locals worry the feral dogs, who were frequently infected with rabies, would inhibit the economic recovery in the wake of Covid, so sometimes the dogs were poisoned. She said she was a writer, that New York would have killed her if she hadn’t left eight years ago. She’d decided to gift herself the retreat for her birthday. In turn, I confessed that I was burned out and really struggling with the state of the world, that I was working through some things and realizing the silence at times was really hard and at times lovely and I wished everyone could do it. We talked about how the answers are within us. How it’s hard to trust that things will get better, but all we can do is be the best versions of ourselves.

And then as my eyes welled up, I told her it was the anniversary of my father’s death. And she said she had lost her dad too, and she assured me he was with me. She hugged me, and it felt awkward there in the hot spring pool, but it also felt so good after no physical or verbal contact with anyone for so long. She asked if he ever sent me signs or gifts. And I thought about the vision I’d had in meditation that morning, and I said oh, yes. And I thanked her for letting me share that. She said maybe the blue flower I’d found on the pathway and had given her was a sign from my Dad. And I admitted the thought had occurred to me as well.

Our time at the hot springs was nearly up, so we made our way to the van meeting point. The Kiwi asked where I was from in the states, and I said I lived in Arizona but grew up in Minnesota. She said she could tell by my accent because of the movie Fargo.

The New Yorker said she couldn’t hear my Minnesota accent. And then she and I discussed how important it is to do the hard things, to be in silence and work through your garbage. And how so many people don’t, and as a result, they make fear- and anger-based decisions. And I said it was hard; the other day I had realized what an asshole I am, and that night at the firehouse, where we write down and burn apologies or “sorry papers” to those we have wronged, I had a lot to toss into the fire.

She nodded knowingly, “We’ve all been there.”

The Kiwi lamented not having any cash for a cup of coffee. She brought it up three times. I had no cash, but the third time she mentioned I became inspired, and felt conspiratorial. I explained that it was the anniversary of my Dad’s passing, that he had always loved coffee, drank it from sunup to sundown.

“I have two packets of instant coffee back at the retreat center.” I said, barely above a whisper. “I would love to have a cup of coffee with you in his honor.”

Upon our return and after lunch, we sat on her balcony overlooking the rice fields and volcanoes. I pulled up my father’s photo on my phone, his military photo, where he was young and strong and perhaps fearless. And I turned his face to the idyllic scene. And we drank coffee in silence, and it felt sacred to me. I know Dad would have approved.

It was night seven of thirteen. The outing was what I’d needed that day, so I could talk about my Dad, so I could make the day one of some joy instead of just sadness. It had allowed people to be with me in that space, to hug me, to comfort me, to share coffee in his honor while gazing out at an incoming storm sweeping over volcanoes and rice fields and ducklings and lands he never saw and likely never dreamed of seeing. And yet he was there, suspended in that delicate moment. He was there.

Late that night when the lights were out and I was tucked into bed under the gossamer drape of a mosquito net, a firefly darted into my room, startling me. It seemed a person was there, perhaps an apparition, or at least my insomniac mind perceived it as such. It immediately resurrected a childhood memory of Dad, standing in the doorway of my bedroom in rural Minnesota when he was watching over me as a little girl, and all I could see was the lit tip of his cigarette, suspended in the darkness.

Three days later, I went back to the hot springs. There were just two of us, and my co-retreatant made a zipper motion over her lips, so I knew she intended to stay in silence. I soaked in the bubbly hot spring pool near the river, and a flock of little birds barely bigger than hummingbirds landed all around me. I stayed perfectly still to encourage them so that I could enjoy their company. The pool bubbled up and a droplet of water landed in my mouth. It tasted fresh and clean.

The next day I wrote in my journal, “Sick as a dog and shitting like a mink.”

I had thought I’d worked through the things I needed to take on during my silent retreat. I’d even checked out books from the library, allowing my brain some entertainment other than its own thoughts. After all, had I not worked through issues related to my own mortality? Had I not healed lingering pain and resentment from the pandemic and how humankind had failed one another? Had I not recognized patterns within myself that harmed others? Had I not grieved and even found joy while mourning my father? I’d summited these spiritual mountains one after the other, and had descended into a greater sense of wholeness. It was good, hard work, but I’d done it and assumed it was now time to enjoy the retreat. One cannot labor nonstop, whether the work is physical or psychological; fatigue sets in and rest becomes crucial. I was ready to rest.

But I had mistaken the grace of a brief respite with being done with my work. My spirit had merely let me catch my breath before the real work began.

The illness overtook me shortly after lunch, when I’d bent over the toilet in my room to reject carrot shards swimming in golden turmeric, gagging sounds from my own throat echoing into the jungle.

After days of honing my mindfulness skills, I was painfully present for every turn of my stomach, every cramp, every dry heave. Worse, no one can give you comfort in silent retreat, not really. You are alone in your suffering. I was powerless to do anything but ralph and shiver as the jungle beasts sang in the background. I took comfort in the knowledge no humans were likely to hear me vomit, my lone neighbor had moved on. Had I stayed in the more austere room, I would have had an audience of up to 16 people.

After eight aching, feverish hours of purging everything in my body, I waited for the sweet kiss of death. But that selfish whore refused to come for me. So instead, I walked my weary body up to the front office, a mile-long effort which felt herculean. I figured I should let the retreat center staff know I’d fallen ill. The worker at the desk offered me what felt like hippy bullshit cures: colloidal silver mixed with water and a green jelly to rub on my belly. All I wanted was Cipro, but the jungle was fresh out. She gave me the bottles to take back to my room, along with a cup and spoon. As my illness progressed day after day and I grew weaker, there was talk of taking me to the “small hospital” on the island if I didn’t improve, or maybe finding me some coconut water. Neither came to pass.

I felt incredibly sorry for myself. I longed not for a hospital bed, but to be home in my own bed, with my mother kissing my forehead and saying “poor baby,” in that compassionate way that only she can, and my husband fretting over me, bringing me cool, wet washcloths to draw down my temperature. As the fevers came and went, the silence became unbearable. My brain continued to work on issues I’d thought I’d lain to rest, and the intensity of the work paired with the illness felt almost like a shamanic ceremony. Solitude and silence allowed me uninterrupted, unmonitored time to ponder every ache, pain and vomiting spell, to anticipate how near I was to the end. Not far from my room that night, the fire at the firehouse was going strong, with retreatants presumably burning their sorry papers. Periodically pressure would build up in the bamboo they set aflame, then burst with a terrifying boom in the midst of the silence.

Two nights and two full days after the illness had set in, I had the chills. I pulled on my morning yoga clothes and a lightweight hoodie I’d packed, and climbed back into bed. I hated that I couldn’t even do a quick online search of colloidal silver and its risks or benefits. I could only trust, and take it, and rub the green jelly on my stomach, and hope.

It was another sleepless night. In the morning as the gong rang out in a call to class, I had a fever dream there was a man playing guitar in my room. A housekeeper came by to check on me, and I told her I was alive, though I still felt feverish. She had brought some cookies and fruit and juice, none of which I could bear to eat. I felt sapped of all of my energy, with only the smallest flicker of lifeforce.

The staff continued to check in on me, bringing me food and compassion and hugs, but I prayed only to be well enough to leave. I had one last full day, and had little left to give. As a forbidden treat to myself at my lowest point, I powered up my iPod, put in my earbuds and pressed play. What would have been unremarkable under normal circumstances was the most intensely beautiful music I’d ever heard. It was nothing more than a common pop song. But I could feel every note on every nerve in my body, every drumbeat boomed in my heart, and I was overwhelmed and struck breathless by the magnificence of it all.

That night I was able to keep down a small amount of white rice, cooked cauliflower and wontons. A sign in the lodge warned, “sorry disco music,” as there was to be a festival in town. I could hardly hear it and had no energy to care. I took two Benadryl before bed hoping it would help me sleep through the night.

“Solitary confinement when sick is the eighth dimension of hell,” I wrote in my journal. “Let’s drag our weary souls across the finish line.”

The next morning, I pushed myself from the mosquito net as if it were birthing me–a new me. I felt a bit better, even ready to try some food. I’d been craving watermelon. I summoned myself for meditation, though I still felt weak when walking.

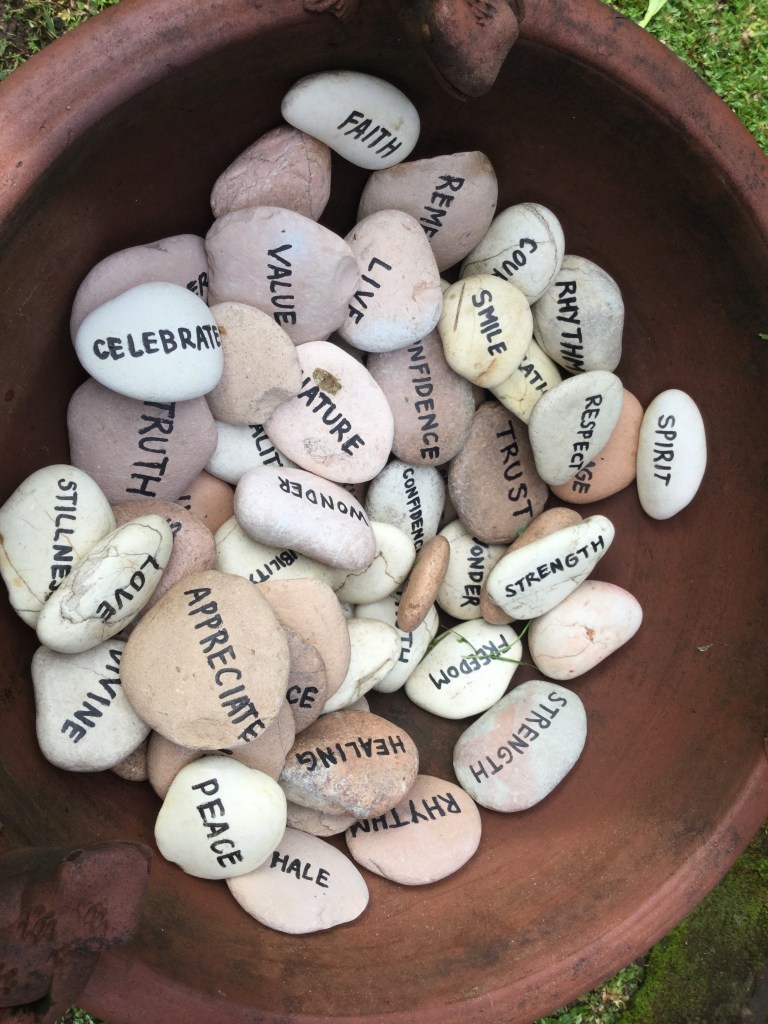

The day was overcast and breezy. After breakfast, I walked the labyrinth, newly manicured with every stone freshly scrubbed. I chose two stones for my intentions, marked with the words: peace and healing. I chose them for me. I chose them for all of us. Then I walked to the goddess temple and sat silently under the shower of holy water for some time, wrapped in a pink sarong. And when I was done, I placed a flower on the goddess who had bestowed the baptism upon me.

I packed to go back to the noise. I felt lighter, in some ways. Perhaps in two weeks of silent retreat I had released some of the anguish I’d accumulated over a half century of life. I’d been able to engage in some deep meditation and contemplation, descending to levels I would never have reached in the so-called real world. Through my fevers I’d even come to terms with some irredeemable relationships, and I had released the desire to keep trying to change them. Would I have gotten there if I’d not been humbled by my illness? Probably not. Instead I let go of the attachment, allowing it to be whatever it is. I wondered if the unfortunate illness was perhaps indicative of all that is left undone. Or maybe I just got a sip of rancid hot spring water in my mouth. Maybe searching for meaning in everything is counterproductive. Then again, maybe it’s everything.

I do believe the world could be a very different place, and maybe a better place, if we all took time to step back and set down the weight we carry: the pain, the anger, the fear, whatever it is we have amassed in our lifetimes. It varies from person to person but in the end it’s all the same. I wish everyone could take two weeks in silence to work through what they will, and to learn to detach from that which no longer serves them. Maybe you don’t have to travel to the other side of the world to do it, but if you do, Bali Silent Retreat, and a room overlooking the jungle, is a lovely place to do the sacred work you have to do to continue your healing journey in this life.

Namaste, my friends. Peace and healing to me and to you.

We’ve been sharing transformational travel content free of charge, ad-free and sponsorship-free since 2011. If you enjoy our content, please consider supporting our work here: https://rollerbaggoddess.com/support-our-work/.

Charish Badzinski is an explorer and award-winning features, food and travel writer. When she isn’t working to build her blog: Rollerbag Goddess Rolls the World, she applies her worldview to her small business, Rollerbag Goddess Global Communications, providing powerful storytelling to her clients.

She is currently working on a collection of her travel essays entitled: Sand Dunes, Sea Salt & Stardust.

Posts on the Rollerbag Goddess Rolls the World travel blog are never sponsored and have no affiliate links, so you know you will get an honest review, every time.

Read more about Charish Badzinski’s professional experience in marketing, public relations and writing.

Discover more from Rollerbag Goddess Global Communications

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.